Untitled (New Plymouth)

E. Mervyn Taylor

Type

- Window(s)

Medium

- Glass

Dimensions

- H1800 x W3300mm

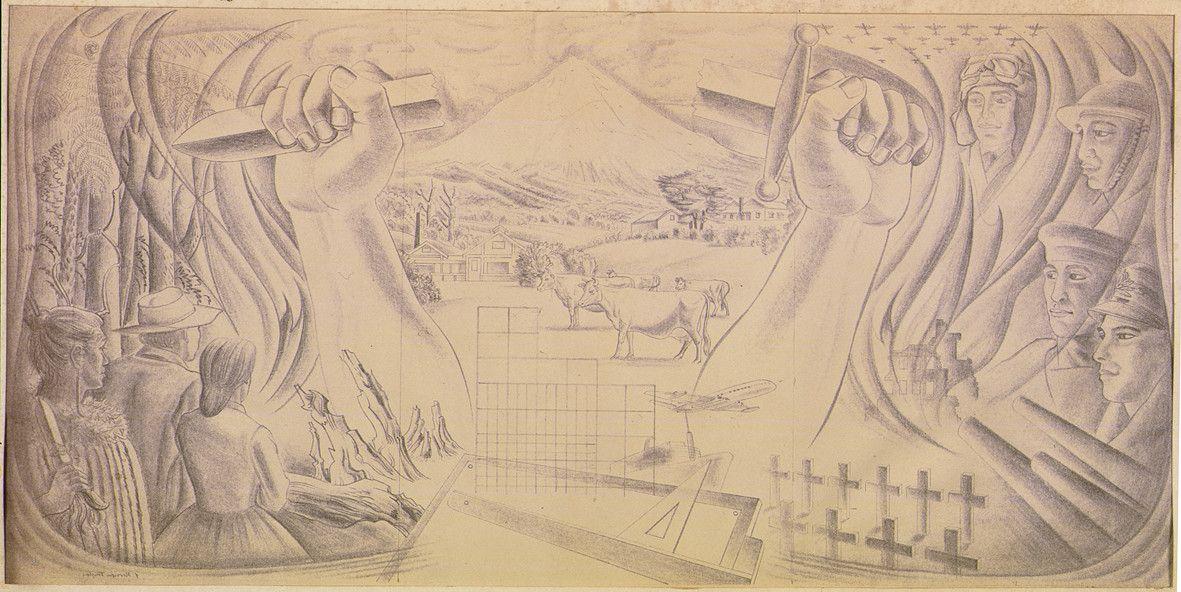

E. Mervyn Taylor, Untitled (1960), Puke Ariki, Ngāmotu New Plymouth

Image: Shaun Waugh, Public Art Heritage Aotearoa New Zealand, 2016

- DETAILS

- MAP

Description

In the years immediately following World War II the New Zealand government offered towns and cities subsidies on locally raised funds to build war memorials. Communities were encouraged to build ‘living memorials’ — facilities such as halls, libraries and regional museums — in contrast to the familiar concrete or marble monuments that were built after World War I.

In the early 1950s the town of New Plymouth decided to use this opportunity to build a war memorial hall and library — replacing the existing ones — and add a regional museum. The local firm Taylor & Syme & Associates (later operating as Taylor & Collins) won the job of designing the building.

Edgar Collins, the architect in charge, wanted a feature wall to be the focus of the actual war memorial. He planned for this to be located where it would be seen by the most people: on the return of the main staircase leading into the hall from the building’s entrance off Ariki Street. Collins allowed space for a mural measuring 3.3 metres wide by 1.8 metres high, surrounded by a dark-green breccia and limestone features, with bronzed lettering above. The location presented a challenge because the scheme for the mural would have to make sense to the eye from two potentially distorting perspectives as people walked up and down the staircase.

By late 1958, the two-year construction process was sufficiently advanced for Collins to select an artist. He chose E. Mervyn Taylor. Furthermore, he realised Taylor’s technique of rendering the design in sand-blasted plate glass would allow the image to be back-lit as a kind of ‘eternal flame’.

As a memorial feature, Taylor’s brief required a commemoration of those who had left Taranaki for overseas war service in World War II and did not return, but in the context of historical Taranaki the design had to refer to both the physical place and its interracial past. Furthermore, the final approval would not be Collins’s but the city council sub-committee’s. This was likely to be a difficult business, he wrote to Taylor, for each of the councillors would be bound to have their own opinions as to what constituted art and what ought to form part of the design. ‘New Plymouth is, conservatively speaking, quite lacking in open minds but we have piloted a number of ideas in this building which are to locals revolutionary, and elsewhere would not appear so startling,’ wrote Collins. Taylor was sufficiently troubled by the location of the proposed commission, and the possibility of official local opposition to his preliminary sketches, to travel to New Plymouth in 1959 and meet with the architect to view the site. He was able to submit his final design by the end of the year.

The sub-committee approved the design and it was created using the technique of sand-blasted heavy panels of plate glass. Once installed, the mural was back-lit with a salmon-pink light — an effect created by white fluorescent bulbs shining on a coloured recess behind the glass.

Text adapted from Bryan James’ essay “An Eternal Flame to Provincialism” in Wanted: The Search for the Modernist Murals of E. Mervyn Taylor (Massey Press, 2018).