Untitled [Wairoa Centennial Library]

E. Mervyn Taylor

Type

- Mural

Medium

- Paint

- Hardboard/HDF

Dimensions

- H3500mm x W3160mm

'Interior, Wairoa Centennial Library' by Duncan Winder (1919-1970), architectural photographer. Alexander Turnbull Library, Te Whanganui-a-Tara Wellington (Ref: DW-0302-F)

Image featured in article 'Centennial Library, Wairoa' in the Journal of the NZ Institute of Architects, May 1963, 30(4: 62-63)

- DETAILS

- MAP

Description

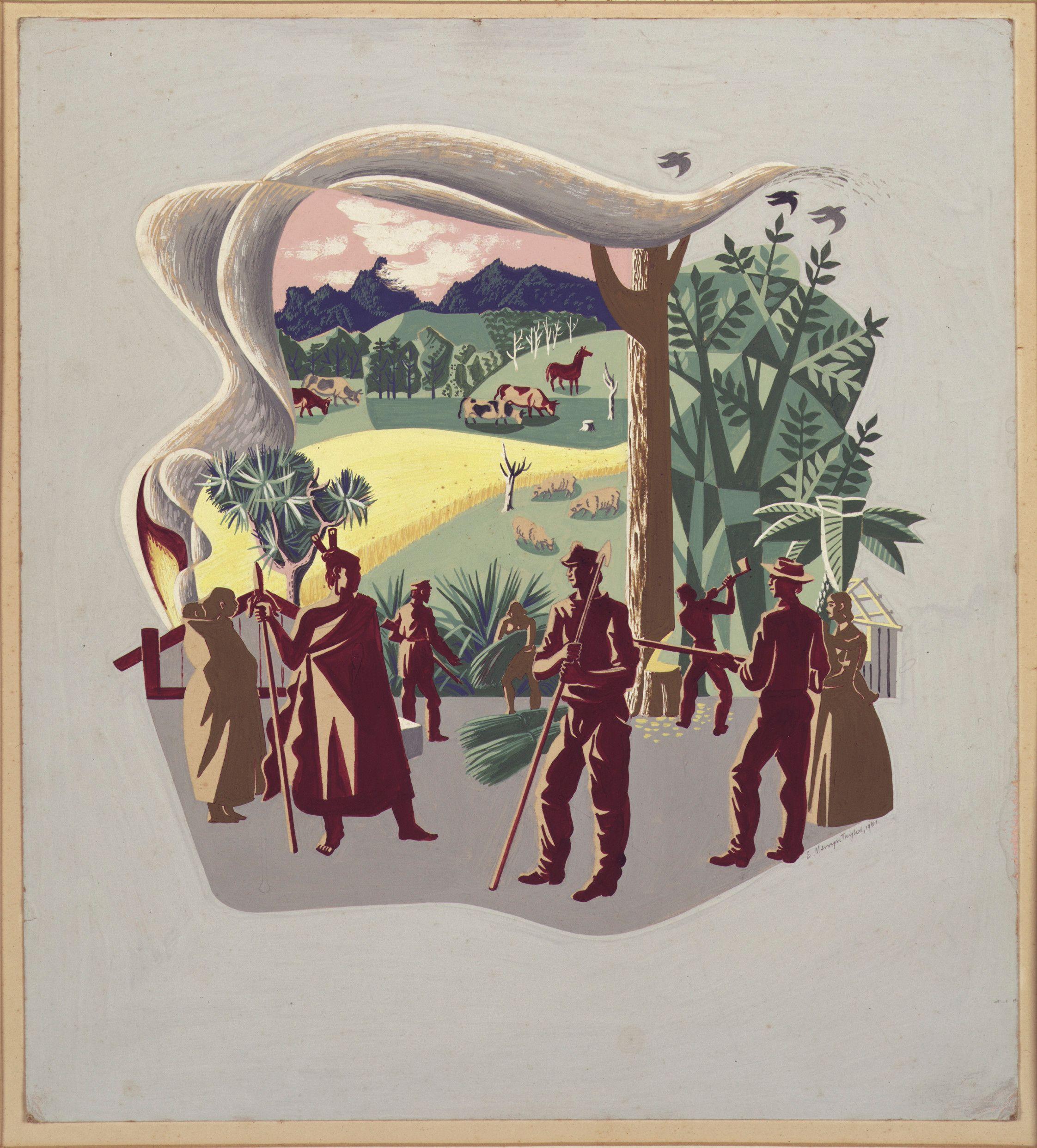

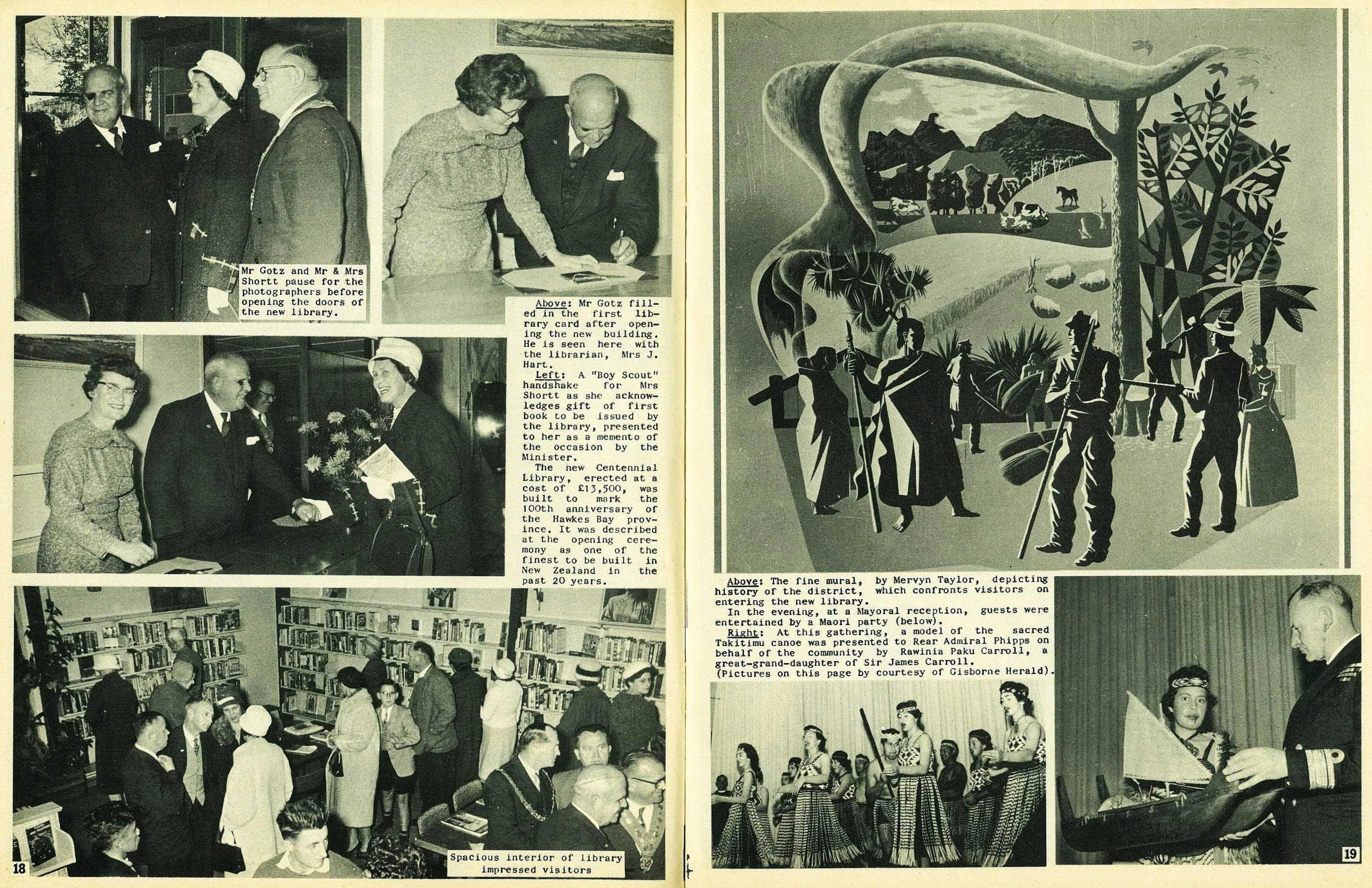

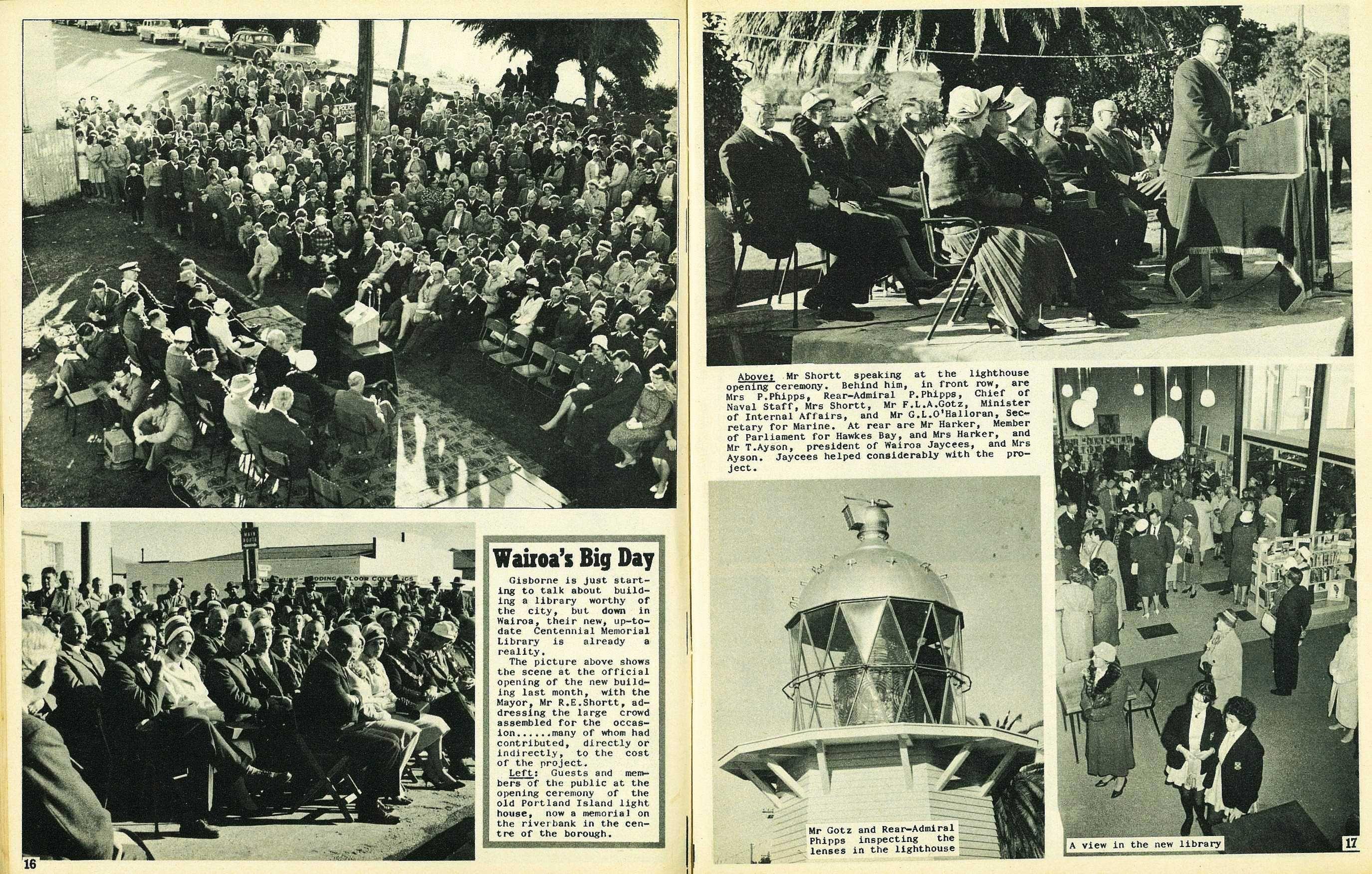

The Wairoa Centennial Library was opened in July 1961. Photographs of the opening convey the mid-century optimism of a town at its peak and detail the building’s bright modern lines. Taylor’s mural, adorning a two-storey central wall, is the centrepiece. Ladies in hats and furs bely a provincial conservatism that was confirmed by Taylor’s son, who remembered being reprimanded by a local policeman for working on a Sunday while helping his father complete the mural.

E. Mervyn Taylor’s Wairoa library mural does not function at all as a picture of the town (missing, after all, is Wairoa’s eponymous river), but rather presents a stylised textural quilt of the journey inland toward the bush. Notes written on Taylor’s initial designs for the library mural confirm this interpretation of the mural as a journey both inland and toward the past: ‘Red Heads, 1 Early Maori, Whalers, 2 cattle and sheep, country mostly hilly, heavy bush, big trees, Moa, cabbage tree, flax, travel on horseback, early fruit centre, wattle & daub huts, wheat, timber.’ The layering is both spatial and temporal.

There is an ancient, primordial quality to that inner landscape that exerts a powerful attraction. The very fact that something older and wilder persists in this place, despite the overwhelming economic pressures of modern agriculture on the New Zealand landscape, is a direct result of local Māori leaders’ concerted resistance to land cessions and confiscations in the 1860s and 1870s. Taylor seems to gesture at this tension in his mural, which was commissioned, along with the building that housed it, to mark the centennial of the establishment of Wairoa township, during the height of colonial confiscations and escalating conflict.

The mural depicts two family groupings facing off: a Māori rangatira is armed only with a taiaha, while four Pākehā men bear two rifles, a whaling spear and an axe. In reality, the local conflict between Māori and Pākehā was far less asymmetrical than this image implies, with Māori embracing all the legal and technological tools of their time to wage a highly innovative and effective guerrilla campaign against the colonial forces. Almost 150 years ago the final chapter of New Zealand’s land wars were played out largely in the Ruakituri Valley, inland from Wairoa, against the background of Te Urewera. The events are more complex and polarising than can be done justice here.

Between 2001 and 2002, Taylor’s Wairoa mural disappeared, quietly and without fuss. How could an artwork that was two storeys high and built into the wall of a public library vanish without trace? During a 2001 renovation it was noted that the steep, narrow stairs that provided access to the library’s upper mezzanine were not up to current building code. Their replacement required the removal of the wall on which Taylor’s mural was painted. The panels were removed and put into storage at the old fire station in the hope that a replacement site in Wairoa would eventually be found.

Shortly thereafter, a woman claiming to be a family member came into the library looking for the mural and expressed her dismay at finding that it was no longer there. If the mural was no longer in use by the library, she asserted, it should be returned to the family. With no foreseeable future site for the mural, it appears that council staff honoured her request, either sending the mural to an address she provided or allowing her to take the work.

Fifteen years later it has been discovered that Taylor’s family know nothing of this incident. Those who might have been involved with returning the work to the ‘family’ have since passed away, and no records of the circumstances of its return have been found. In late 2016 a reward of $5000 was offered for information leading to the mural’s rediscovery and one year later, in late 2017, it turned up. The people who have it wish to remain anonymous — but it is found, and it is safe. Its story, however, resonates with a theme that has emerged across the journey of this project: that New Zealand’s historic public art is in need of serious attention.

- Text adapted from Joyce Campbell’s essay “Layers Upon Layers” in Wanted: The Search for the Modernist Murals of E. Mervyn Taylor (Massey Press, 2018).

The mural was put up for auction in November 2023. Read an article written in response to this event here.